I wrote about reading James Baldwin and unpacking language and power with my 10th Graders earlier this month, and now I’d like to share a few of their final projects in that unit.

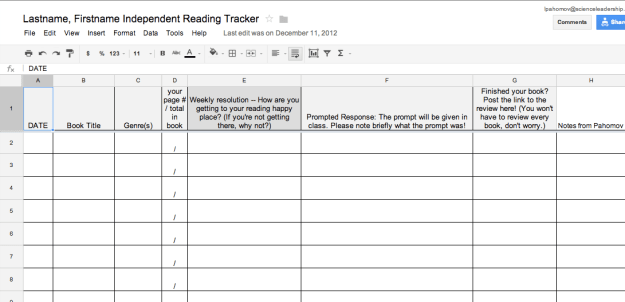

Here’s a snippet of the instructions:

Your language autobiography will investigate some of the themes from our language unit and relate them to your life. The expectation for this paper is a polished piece of writing that combines personal experience with larger analysis and reflection.

This is NOT a traditional “thesis paper” — you will share a deep understanding about yourself, but you want to lead your reader to that instead of sharing it in your intro paragraph.

Your paper must contain at least one descriptive scene from your own life — and this will probably include dialogue — along with deeper analysis. You must also incorporate a quote or idea from the language essays we are reading together.

If you’re familiar with the diverse makeup of our student body, you can imagine many of the relevant subjects that many of our students explore. Code switching, slang, foreign languages at home, neighborhood accents, are all topics that students often gravitate towards.

Every year, though, there are also students who hesitate when the assignment is given. They don’t see anything noteworthy or unusual about their language; they have never experienced it as a place of conflict. They might be white, or middle class, or sound like news broadcasters, or something else entirely — it all depends.

This unsureness can turn into a situation where the majority or dominant culture feels under-celebrated, like they have no unique experience. (This is, I think, where the motivation for things like “White Studies” comes from.) The privilege and power might be something to be defended, or ashamed of, instead of examined.

I am blown away every year when kids actively resist this path, and take the time to explore their individual stories. Whether they’re coming from a place of struggle or a place of comfort, each can be examined in the larger context of society. Students do a great job getting past cliche and to real meaning.

And with that, I give you two Digital Story versions of this project. Both take on this project through the lens of school — and present the opposite, but equally relevant sides of the same coin.

“You Have Nothing To Hide From”

“Listen to Our Words”

Thanks to Josh Block for handing me both the original assignment and the Digital Story remix.