Last week, I posted about students taking the Harvard Implicit Association Test (IAT) in my classroom. A common question I got in response to this post was, “what did you do to set up your students so they could participate in this activity successfully?”

The big answer is that SLA does a lot to make students comfortable with tough moments and difficult conversations. The small answer is that we did several activities in the days leading up to the IAT that primed students to be open and vulnerable.

On day one, I asked them to simply define bias, prejudice, and stereotype, and then create a poster that visually clarified the differences between these terms — without perpetuating any of the stereotypes or myths that get tossed around these days.

This set a valuable precedent: we can mention common prejudices and stereotypes, but proceed with caution, because the way we talk can impact how people are affected by these ideas, even if they are not being presented as true.

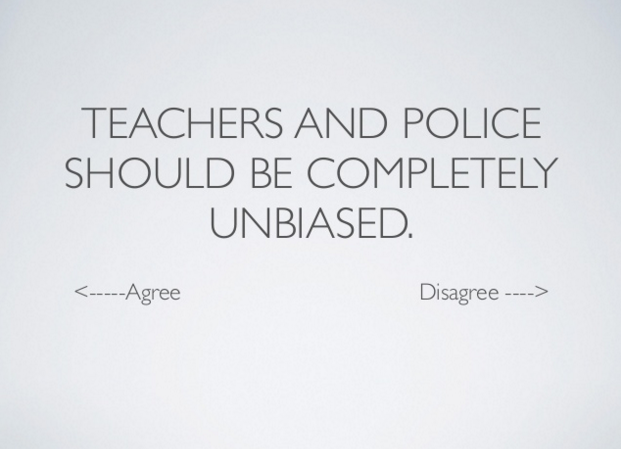

On day two, we played one of my favorite games, which I call “Where Do You Stand?” The room gets cleared, and I project a series of prompts on the board. If you agree with the statement, you move to the window side of the room. If you disagree, you move to the wall.

The prompts, as you can see below, move from more personal and straight-up qualitative statements to more nuanced and complicated aspects of our society.

Once students have picked a side (and no, I don’t let them stand in the middle), it’s time to go back and forth and have folks try and convince their peers to come to their side. Students can switch at any time. One of my favorite scenarios is where just one or two students pick the less popular side of an argument–but by the end they’ve got more people thinking their way.

I think it’s also important to mention that, as the teacher, I hardly say anything during this discussion. Apart from reading the prompts, and an occasional “tell us more” nudge, I am just listening. Because everybody is an active participant, everybody has a stake in the outcome — and the fact that people can move at any time keeps interest up as the debate unfolds.

This game is consistently cited by my students as one of their favorite activities in my class. It consistently gets students who rarely speak to open up, sometimes because it gives them a concrete action they can describe (“Hey [student], why did you switch sides?”). In a class with lopsided participation, requiring everybody to comment once before somebody can speak again can work.

Do you play similar games in your classroom? What’s your experience with them?